The following article was published in Fortune Magazine in 2013. It is still relevant and inspiring in 2023.

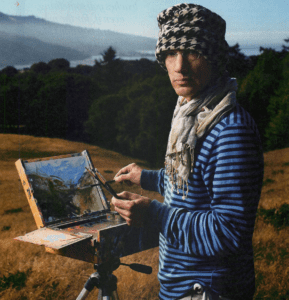

Above: Sir Michael Moritz, painting, on a hill above the Bolinas Lagoon near San Francisco, CA

Sequoia Capital’s Chairman on what it’s like to discover a sublime pastime in middle age.

MEL BROOKS used TO SAY that filling a blank page with words is hard work. Clearly, Brooks had not encountered a primed canvas propped on an easel. Neither had I until I was about 40. At my high school, art class was considered the preserve of the dunderheads. I definitely could not draw, and my experience of painting was limited to shelves, walls, and trim (with the Jackson Pollock effect reserved for floorboards). It wasn’t until about a dozen years ago, after happening upon an article Winston Churchill had written in the 1920s, “Painting as a Pastime;’ that I made my first trip to the art store. Churchill describes how, without any prior training or any demonstrable proclivity, he took up painting at age 41. This hobby became an all-consuming passion that (except for World War II, during which he painted only one picture) accompanied him into his dotage. Churchill’s article, later transformed into a book, must have stirred some of my latent, midlife longings. Most people say they cannot paint, but as with most things, we all can. It’s no different from any other pursuit-playing music, coding software, acting, translating, designing physics experiments: We just don’t do it as well as the experts, and at some point, a natural gift separates Michael Phelps from the early morning swimmer, or Goya, Velasquez, and Picasso from the everyday dabbler. As with so many things, painting is about overcoming inhibitions. The consequences of an unsatisfactory painting are only frustration and disappointment-nothing worse. The canvas will not punch you in the eye or bruise anything beyond your ego.

Like all duffers, I made my share of early mistakes. At the art store I bought almost every different shade of oil paint, little realizing that half a dozen tubes are sufficient to generate almost every hue and intensity imaginable. When I first heard about mediums-the art vernacular for liquids used to thin paint-I assumed they were arcane devices that channeled the artistic spirit. It’s easy to become enamored of the lingo of painting-especially the names of paints such as cadmium yellow medium, Prussian blue, alizarin, viridian, and Payne’s gray-and develop fondness for favorite brushes. I played around with watercolors, but as soon as I discovered that oils offered more room for error, I switched. My first attempt at a completed picture was to copy-on a canvas that was intimidatingly large-a painting by R.B. Kitaj. Looking at it recently, I noticed that my crude rendering was even worse than I had remembered.

I didn’t make much progress until I tripped across Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, by Betty Edwards, a reassuring guide to the art of drawing (and painting is little more than drawing with brushes) first published about 40 years ago. I worked through the exercises in the book and found they, helped because drawing is the vocabulary for all art. Lessons (though I probably haven’t taken more than a dozen formal ones) accelerated my progress. They helped me master the mechanical rudiments-such as mixing paint and fiddling around with hues and intensity-but more important, showed me how to develop a painting in layers and, odd though it sounds, apply more paint.

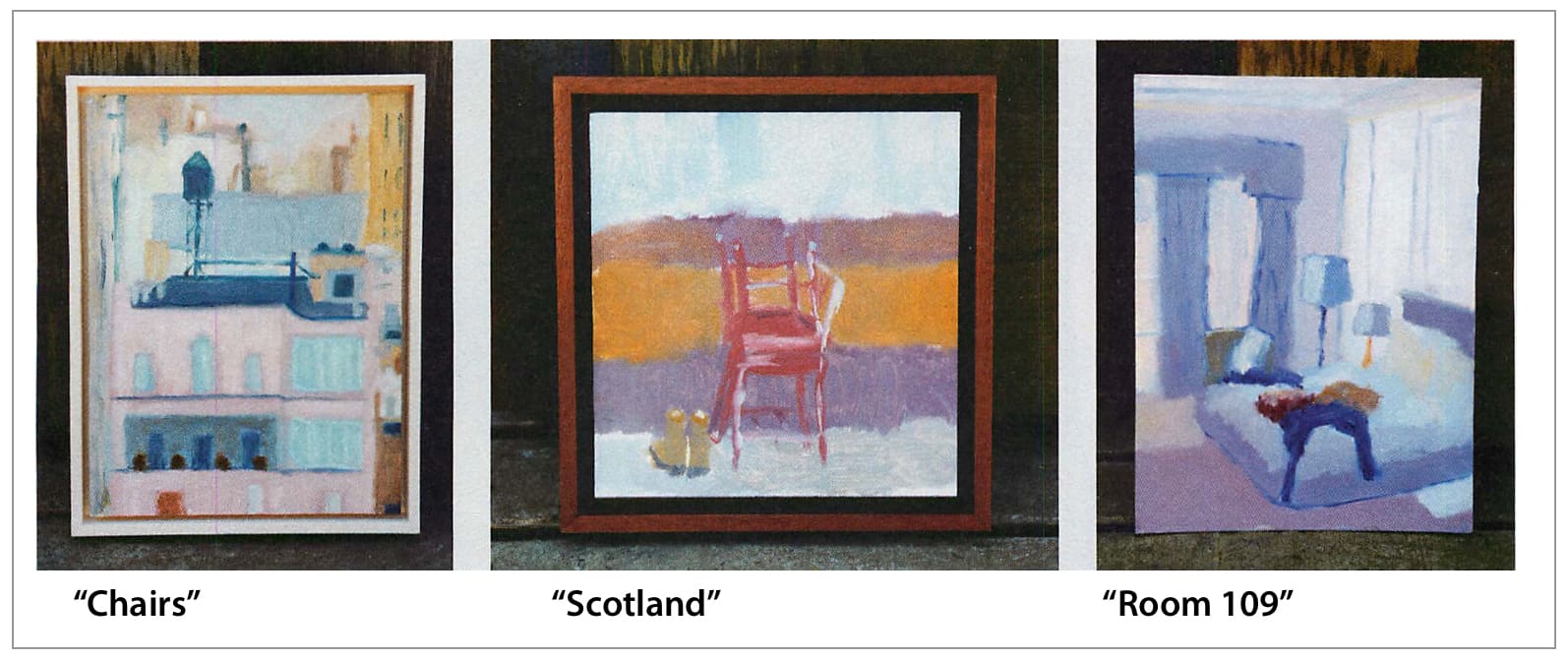

Last summer I spent a wintry week in the west of Scotland with 30 students, some just one-third my age, from the Princes Drawing School, now the best school of its kind in the United Kingdom. Not only did it rain every day, but even worse, there were only two colors in the surrounds: gray and green. We worked for seven days, from nine in the morning to six in the evening and watching people’s different interpretations of the same views and listening to the nightly critiques were educational.

Painting sharpens your gaze. Every view and person become an object of scrutiny. Painting makes you look at things more intently and, best of all, conjures up a time and memory far better than a photograph, postcard, or Instagram snap. If you look at a painting you made, you will remember the time, the place, the weather, the people you were with, and the mood of the moment. That’s something the smartphone does not do. Painting also shuts out the world. If you are painting outdoors, the passage of time is marked by the changing length of the shadows. There is little better than rising long before breakfast and disappearing with an easel. It’s also pleasurable to stand in a hotel room-while others race around tourist sights-and quietly paint a view. There is nothing that beats the sense of fulfillment that comes from completing a picture in which everything seems to go right. This sensation overwhelms all the frustrating outings when all goes wrong, the easel topples in the wind, or the painting falls short.

“Every painting teaches you something, even if, for the most part, you don’t like what you painted.”

Leafing through magazines, I’ve discovered any number of fellow travelers who have gained solace from this solitary pursuit. It turns out that Bob Dylan and Ron Wood are both avid artists. Morley Safer, of 60 Minutes fame, has painted for a long time, as has Tony Bennett. More surprising, painting has also attracted some hard-boiled politicos. Don Regan, Ronald Reagan’s Treasury secretary and longtime CEO of Merrill Lynch, discovered painting in his retirement and ruefully admitted that if he had done so as a younger man, he would have played far less golf and consumed less whiskey. More recently, I noticed a photograph of another retiree proudly standing beside his easel, George W. Bush.

If you paint outdoors, your skin thickens, not because of the elements but because passersby become curious. I like to paint early on weekend mornings in a little Northern California coastal town where my easel seems to attract cigarette smokers out for a lung-cleansing stroll, dog walkers, and better still, a couple of local fishermen, who kindly give me fresh abalone or salmon. Everyone has a comment. Most will stare at the canvas and ask, “What are you painting?” One lady told me, “My aunt left me her palette. Yours looks just like hers.” Occasionally, a child or two will saunter along, and it’s always fun to let them dab some paint on the canvas.

I try to take paints whenever I travel, and this just invites comments and behavior of a foreign nature. A hotelier surveyed one canvas and my paint-spattered clothes before observing, ”Your shorts make a great piece of abstract art. I could sell those.” A couple of years ago on Ile de Re, a bucolic island slightly north of La Rochelle, I was painting in a harbor town when I got jostled away from my easel by French tourists eager to inspect my work and voice their views (which were less charitable than Californians’). Last summer I was offered my first commission, a German who owned an apartment on a small Greek island and must have had one or two bottles of retsina with lunch asked me to make a painting of his home. It’s little wonder that the British artist Stanley Spencer, known for his imaginary biblical paintings conjured up in Cookham, a village about 25 miles from London, used to dangle a sign politely asking people not to distract him from his work.

Procrastinating while painting can be costly. Last fall I began painting the shapes and shadows of a ramshackle concrete making plant, which for many decades had been a permanent fixture beside a road in rural Marin County (California). I’d made the early morning outing five or six times and felt the painting was one step away from completion, but for the last couple of months I had failed to finish it. Two weeks ago, I was cycling along the road, eager to catch a glimpse of the plant, only to discover, to my horror, that it had been torn down. Now this unfinished painting stands propped against a wall, and my painful tale prompted one of my sons to say, “Keep this up and one day you could be the world’s most famous unknown artist.”

Fortune Magazine, July 22, 2013